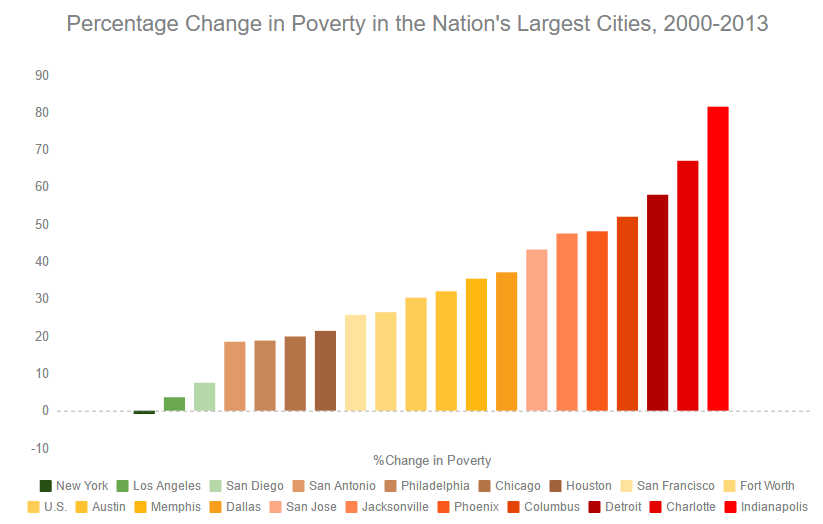

In the wake of the Great Recession, poverty rose nationally and in all the largest cities, except one: New York City.

How was New York, of all places, able to defy national trends and make progress in the fight against poverty? As Linda Gibbs and Robert Doar detail in an essay series for Washington Monthly, one key was that the Bloomberg administration, of which they were a part, focused on experimenting with new ideas and using data and evidence to scale up successful initiatives and terminate failures.

Even today, after the recession, and the start of another administration, the city maintains a smaller share of residents below the poverty line than in Los Angeles, Chicago, Phoenix and Houston, among other large cities.

According to the authors, who are now senior fellows at Results for America, a national organization committed to using evidence-based solutions, for community and family issues,

The first step in New York City’s strategy was to create a “laboratory” for experimentation. In 2006, (New York City Mayor Michael) Bloomberg launched a new citywide apparatus to fight poverty—the Center for Economic Opportunity (CEO). Over the next several years, CEO would roll out more than 30 new initiatives, each to be tested, each with an evaluation strategy, and each taking a risk.

Some of these efforts would prove controversial, such as Family Rewards, a program that provided cash payments to the poor if they took such positive actions as sending children to school. Other efforts – such as a program called “Paycheck Plus” – was aimed at tackling a growing conundrum: falling work rates for low-skilled men. As Bloomberg once noted, “Fathers are missing from our strategy to drive down the poverty rate.”

Another key element of the city’s strategy on poverty was a commitment to evidence and data. Many of the ideas proposed by Bloomberg and implemented by the CEO would take time to reach fruition; and some would succeed, while some would not. But at every step of the way, we made a commitment to measure the results and to learn from both our failures and successes.

For example, the effects of the Family Rewards program were, in fact, “more modest than had been hoped,” according to a 2013 report by MDRC, a nonprofit research organization studying the initiative. But rather than being discouraged, Bloomberg wore this failure as a badge of courage and used his muscle to scale back or terminate what didn’t work.

On the other hand, low-income participants in “Paycheck Plus” are punching the time clock in New York City with some extra cash in their pockets because of bonus payments created by the program – with so far promising results. But like all CEO initiatives, the program is funded through a closely monitored “innovation account,” and control of program resources will not be handed over to the implementing agency until results demonstrate success.

Read more from Robert Doar and Linda Gibbs about the effort to reduce New York City’s poverty rate.