When you wonder whether the 401(k) revolution was a mistake, you have to first ask yourself, what was the 401(k) revolution? That was the move beginning in the late 1970s from defined benefit plans to an employer-sponsored retirement savings that allows workers to save and invest pre-tax payments and pay taxes when they withdraw the money after retirement.

In 2017, people under age 50 are allowed to set aside $18,000 of their income in 401(ks)s while people 50 and over can add another $6,000 annually. Employers often match a percentage of the contribution employees make, and the money goes into market products that compound over time.

And boy do they. The average 401(k), which obviously grows in later years when people earn more, was around $120,000 last year, and those participating in a 401k for at least 10 years have average balances of $251,600.

Yet, the creators of the 401(K) lamented to The Wall Street Journal this week that they were not happy with the way the whole thing turned out. They didn’t want it to be so successful, apparently, because they wanted 401(k)s to supplement traditional pensions not replace them, and they decried the fees associated with investing in an uncertain stock market while people are also living longer.

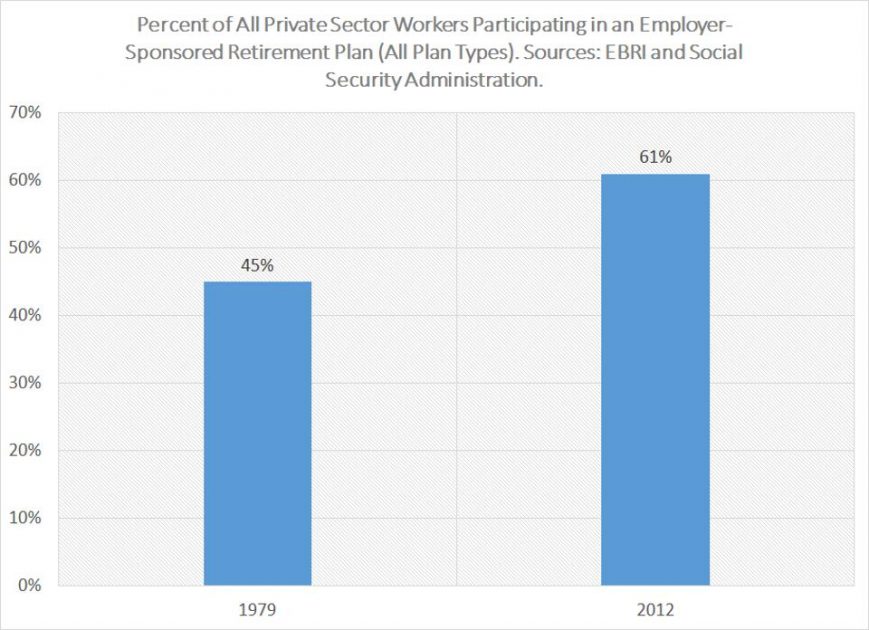

Given that more people are now invested in their own retirement plans than ever before — 61 percent today compared to 45 percent when pension participation peaked in the 1970s — and that these plans are turning around benefits at high rates — since 1984, inflation-adjusted benefits per retiree have nearly tripled — the question to ask is why is this considered failure?

Former Social Security official Andrew Biggs always offers the deep dive on how to count the money. And his analysis suggests all the hand-wringing about retirement savings is a bit overwrought.

The Journal article features a nice chart – under the headline “Savings Struggle” – showing a declining U.S. personal saving rate since 1970. Some might take that falling saving rate as denoting that workers are putting away less money for retirement. Actually, not. The reason is that the total personal saving rate also includes the amounts that retirees are drawing down from their savings (or DIS-saving) , which lowers the saving rate.

And guess what? There are more retirees today than in the 1970s – one-third more, relative to the working-age population. As I’ve pointed out, the total personal saving rate says very little about retirement saving adequacy because, over a person’s full lifetime, their personal saving rate should be zero.

So what are we to do? Start by trying to figure out how much working-age Americans are saving for retirement and whether that amount has gone up or down. … In 1975 – the peak year for traditional pension participation, for those playing along at home – total pension contributions equaled about 5.8% of wages, while by 2013 contributions has risen to 8.3% of wages. That’s a 43% increase in the amount that’s getting set aside in retirement plans, even after accounting for the growth of incomes.

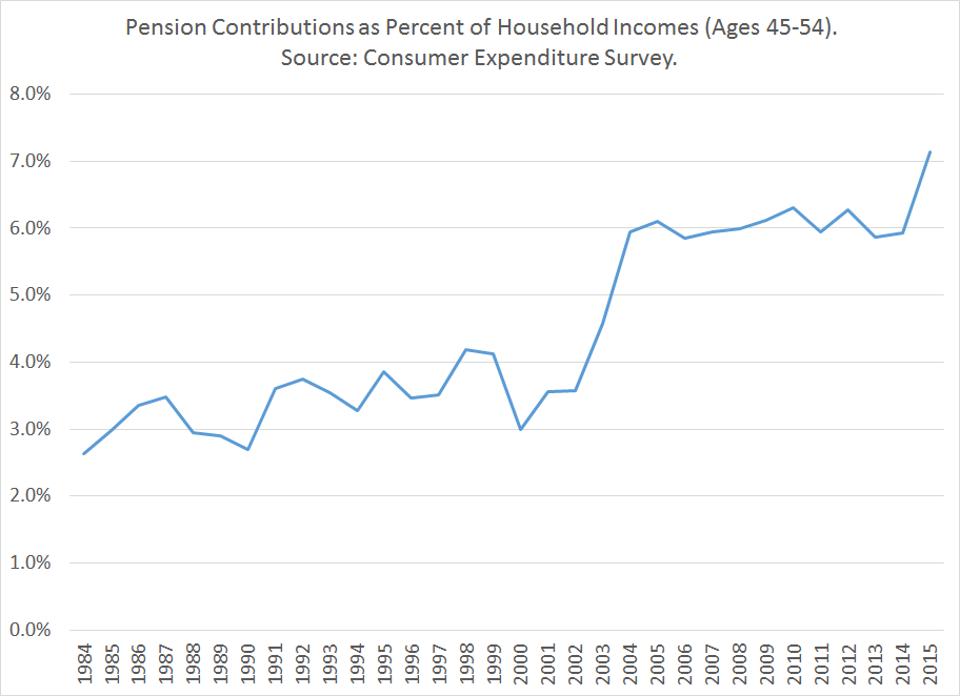

Or we can look to the Consumer Expenditure Survey, which tracks how much households contribute to retirement plans from their own incomes, a figure that excludes employer contributions. The survey aggregates Social Security and pension contributions together, so I pulled out the Social Security payroll tax which rose slightly from 1984 to today. Despite the increase in payroll taxes, household pension plan contributions rose from 2.7 to 7.1% of incomes (for households aged 45 to 54, which are the prime saving years).

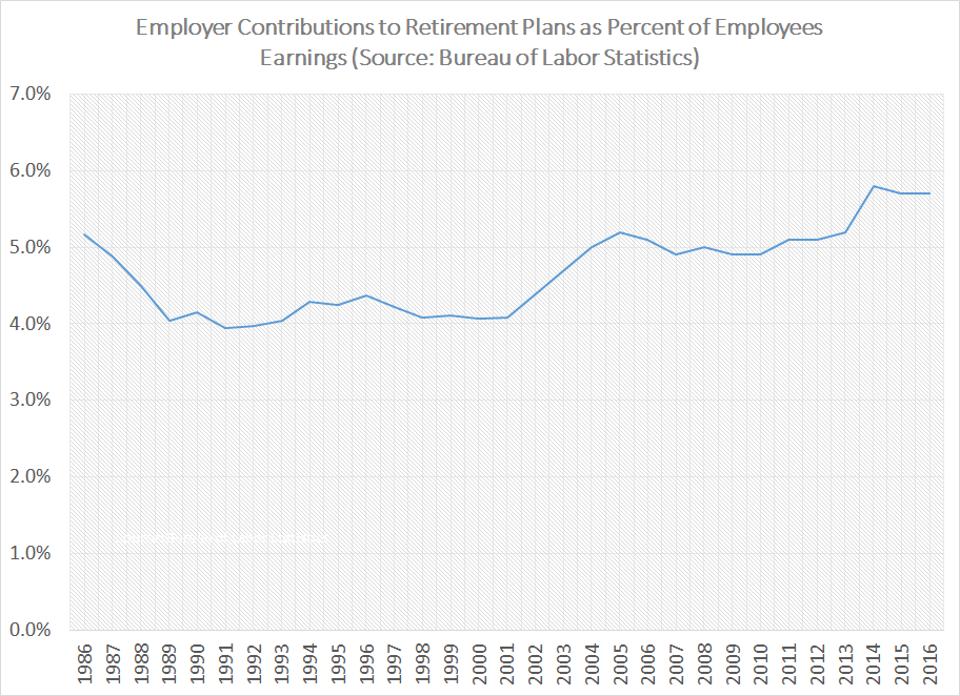

But maybe households are contributing more to their retirement plans only because their employers are contributing less? Um, no. The Bureau of Labor Statistics generates data going back to 1986 for employer contributions to retirement plans. While employer contributions declined from 1986 to 1989, today employer contributions are 10% above their 1986 level and 38% above the average from 1989 to 2001.

Okay, so retirement savings are increasing. But maybe it’s only the rich who are participating in 401(k)s while everyone else gets left behind. Actually, participation in retirement plans today is substantially higher than it was back when traditional DB pensions ruled the world. Statistics aren’t great, and in particular the popular Current Population Survey isn’t great at catching whether employees are offered a retirement plan and whether they participate. Instead, the Social Security Administration looked at workers’ tax records, which record whether they or their employer contributed to a retirement plan. SSA found that in 2012, 61% of all workers participated in a retirement plan. According to data gathered by EBRI, back in 1979 – before 401(k)s took root – only 45% of workers participated in a retirement plan. And the news may be even better than that: if we look at the household level and leave out the poorest households — who will and should rely almost entirely on Social Security — most are saving. In the Survey of Consumer Finances, 89% of households aged 30 to 64 with per capita earnings in excess of $20,000 have either a 401(k) or IRA-style account or some entitlement to a traditional pension benefit.

So to sum up, we’ve got more workers saving for retirement and they’re saving larger amounts. And that’s your 401(k) failure?

Biggs adds that claims of retirement incomes stagnating due to high fees or individuals’ inability to invest are wrong, and points to a study that shows that “from 1984 to 2007 annual Social Security benefits for the median household rose by 25 percent above inflation. But incomes from private pensions increased by 141 percent. That’s one hundred forty-one percent, people. Total retirement incomes for the median household rose by 58 percent above inflation from 1989 to 2007.”

Biggs acknowledges that the retirement system has some problems, but notes that the history of the 401(k) isn’t one of them.