What is the future of traditional religion in this country? This question is discussed constantly across America, from dinner tables to graduate seminars to think-tank conference centers.

You may remember a 2015 Pew reportthat was advertised as bad news for traditional Christianity. The report helped popularize a now-famous phrase: the “rise of the nones.” It showed a big increase in the number of Americans who identify with no religion at all. Since 2007 alone, the ranks of these “nones” grew from 16 percent of America to almost 23 percent today.

That makes “unaffiliated” the second largest of all religious groups — just behind Evangelical Protestants, just ahead of Catholics, and well ahead of mainline Protestants and all other faiths. A huge sea change, right?

Maybe not.

Late last year, the well-known religion scholar Rodney Stark released a new book titled The Triumph of Faith. As you can guess from the title, he doesn’t agree with the conclusion that many are drawing from the Pew paper. But he doesn’t directly dispute the “rise of the nones” thesis.

Instead, Stark combines that result with another, seemingly contrary trend. He notes that over the same years when the number of officially “unaffiliated” Americans swelled, church attendance did not significantly drop. Furthermore, the percentage of self-declared atheists did not seem to increase. What can explain this paradox?

Stark solves the puzzle by arguing that almost all of the new “nones” were Americans who already weren’t attending church much — they just held on to religious labels. As the broader culture around them secularized, the social pressures that once urged nominal believers to self-identify with faiths they didn’t practice were worn away. So, by Stark’s logic, the dramatic Pew report and the “rise of the nones” actually tells a duller story: people who really weren’t religious just stopped telling pollsters they were religious.

If Stark is right, the recent “rise of the nones” may not imply anywhere near the cataclysmic collapse in the American practice of Christianity as has often been claimed.

WHAT ABOUT RELIGION IN POLITICS?

This is another area where real life proves more complicated than the conventional wisdom.

Through all my years in academia and more recently inside the Beltway, I’’ve often heard arguments thrown around that a tiny minority called the “extreme religious right” have taken over the conservative movement and made it more intensely faith-focused than the supposed “mainstream.” The political left, by contrast, was declared to be much more in line with most ordinary Americans’ worldview. True?

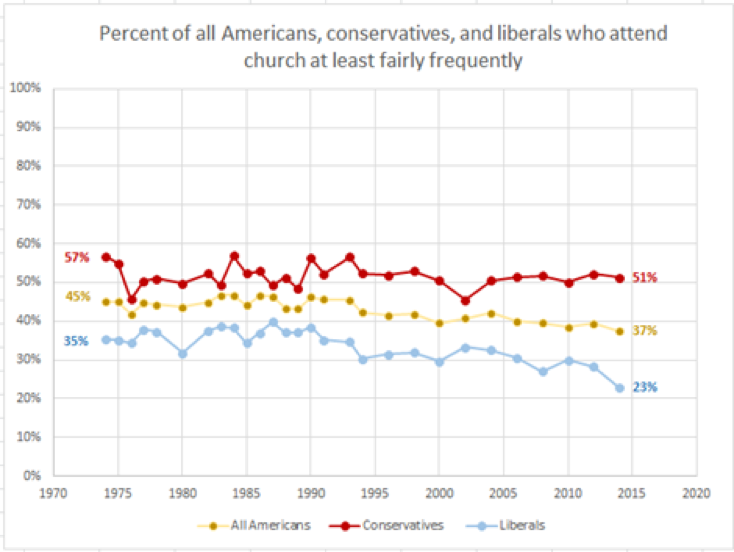

Here’s what the General Social Survey says about the churchgoing habits of liberal and conservative Americans (and the national average for good measure):

The first fact that jumps out is that no group has upped their churchgoing relative to the 1970s. Put aside all the media chatter about the conservative movement becoming the exclusive domain of intense Christians. What we actually find is that 57 out of 100 conservatives were frequent church attendees four decades ago and 51 out of 100 are now.

The much more dramatic shift actually came from self-identified liberals. Their 12-point decline in regular religious attendance doubled the conservatives’ change. At least when we look at simple church attendance, it is the Left, not the Right, that has seen the dramatic shift in religiosity.

Another interesting note — Back in the early 1970s, conservatives were 12 percent likelier to attend services regularly than the general population average, which was in turn 10 points above the average for liberals. But now, each political wing is precisely the same distance (14 points) away from the national average.

The unusual secularity of the left is reinforced when we look to the next generation of liberals. The same GSS data showed that in 1974, when 93 percent of all Americans identified with some type of religion, so did 83 percent of young liberals (aged 18-29). But in the intervening decades, that gap has swelled to a 21-point chasm: More than three-fourths of Americans still identify with some faith, but the odds that a young liberal citizen will follow suit are now barely better than a coin flip.

Again, these are complicated issues that need more analysis than a simple chart. But I’ve always found that straightforward surveys can offer a lot more insight than many suspect.