Ah, millennials. In some ways, they’re very traditional, suggesting that women should stay at home to raise their kids. In other ways, they are very Bohemian, doing as they please when the mood hits. But it turns out, the old-fashioned “success sequence” — a (high school or higher) degree, job, marriage, then children, in that order — is still the winning combination for securing financial well-being, even for this late-day-and-age group.

The term “success sequence” isn’t new. It was coined in the last decade by researchers looking for policy ideas that could help break the cycle of poverty. Of course, it was criticized for pointing out that the cycle of poverty is more likely to be perpetuated for kids born into poorly educated households without two parents and few economic opportunities. It has become rude to point this out even though that’s the problem the research is trying to solve.

But facts are facts, as it were, and a new study by W. Bradford Wilcox, a professor of sociology at the University of Virginia, and Wendy Wang, of the Institute for Family Studies, found that the success sequence holds up as a guidepost for today’s Millennials as it did for Baby Boomers, even after adjusting for a wide range of variables like childhood family income and education, employment status, race/ethnicity, sex, and respondents’ scores on the Armed Forces Qualifying Test (AFQT), which measures intelligence and knowledge of a range of subjects.

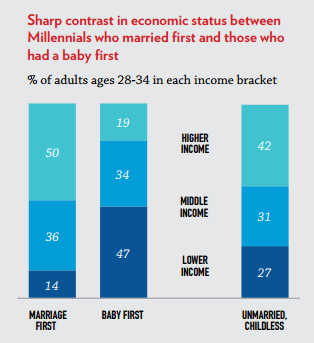

The study found that “diverging paths into adulthood” taken by 28- to 34-year-olds — the eldest of the Millennial age group — produce very different economic outcomes.

Among the findings:

- Millennials who follow the “success sequence” almost always avoid poverty, with 97 percent of Millennials who married first not being poor by age 28, compared to 72 percent who had children first.

- 71 percent of Millennials from lower-income families who put marriage before children made it into the middle class or higher when they reached adulthood. Conversely, 41 percent of Millennials from lower-income families who put children first made it into the middle class or higher when they became adults.

- Among black young adults, those who married before having children are almost twice as likely to be in the middle- or upper-income groups (76 percent) than those who had a baby first (39 percent).

Since 55 percent of 28- to 34-year-old millennial parents had their first child before marriage, the economic and family impacts will be felt for decades.

Millennials are more likely than previous generations to delay marriage and parenthood, but that doesn’t mean that they have to forego the order of education, work, and marriage. Indeed, there’s a reason the success sequence works.

Why might these three factors be so important for young adults today? Education confers knowledge, skills, access to social networks, and credentials that give today’s young adults a leg up in the labor force. Sustained full-time employment provides not only a basic floor for household income but, in many cases, opportunities for promotions that further boost income. Stable marriage seems to foster economies of scale, income pooling, and greater work effort from men, and to protect adults from the costs of multiple partner fertility and family instability.

Moreover, the sequencing of these factors is important insofar as young men and women are more likely to earn a decent income if they have at least acquired a high school education, and young marrieds are more likely to stay together if they have a modicum of education and a steady income. So, it’s not just that education, work, and marriage independently seem to matter, but the sequencing of education, work, and marriage may also increase the odds of financial success for today’s young adults.

Wilcox and Wang point out that there’s no statistical model to perfectly predict a youth’s future success. Some who succeeded came from roots missing those steps. Others who lived in households that followed the sequence ended up in the bottom third of the income scale. Lastly, there’s no conclusive evidence that the “sequence plays a causal or primary role in driving young adult success.”

The researchers also note that it’s easier to follow the success sequence when one is born into it, as opposed to young adults who came from poor neighborhoods, bad schools, and less educated households. It’s also easier to follow the success sequence when one comes from a cultural background that adopts these ideals and expectations rather than those groups who hold these values in lower regard.

But there’s no mistaking that the numbers overwhelmingly favor those who do follow the course, and that’s where both one’s personal “agency” and public policy come into play.

This report suggests that young adults from a range of backgrounds who followed the success sequence are markedly more likely to steer clear of poverty and realize the American Dream than young adults who did not follow the same steps.

Given the value of the success sequence, and the structural and cultural obstacles to realizing it faced by some young adults, policymakers, educators, civic leaders, and business leaders should take steps to make each component of the sequence more accessible. Any initiatives should be particularly targeted at younger adults from less advantaged backgrounds, who tend to have access to fewer of the structural and cultural resources that make the sequence readily attainable and appealing. The following three ideas are worth considering in any effort to strengthen the role that the success sequence plays in the lives of American young adults.